Life is not a battle

But seeing it that way skews our awareness of our body processes and diminishes our ability to participate in maintaining and optimizing our own health

Hello, friends, and welcome back to This Changes Everything, where I share my thoughts about why it matters that viruses don’t exist, “germ theory” is actually the disproven germ hypothesis, and contagion is a myth. My first post outlined my five reasons why understanding this is so important, and the next five dealt with each of those reasons separately. And there is still much more to say! Because this really matters.

There is an underlying paradigm to these false ideas about why we get sick, and it is one of the reasons why getting past these fraudulent notions can be difficult. I’m talking about the paradigm of war, which not only colors our ideas about our bodies and how and why they get sick, but also frames our relationship as humans to each other, to nature, and even to ourselves. It’s a product of a mentality of competition, even to the death, which is embedded in the social and economic structures of the West as well as our thought system, and which, like germs and contagion, can seem to be borne out by our experience and what we witness happening in the world.

However, upon closer inspection and the uncovering of different knowledge, it becomes easy to see that “life is a battle” is a lens through which we have learned to frame our experience, and if we remove that lens, everything looks different.

‘Disease’ as seen through the war metaphor lens

Let’s look at the war metaphor as it is applied to how our bodies work. By maintaining that diseases are caused by pathogenic microbes from outside of us that are always waiting to attack us, the disproven germ hypothesis gives us military vocabulary for how our bodies work and relate to the rest of the biological world. “Viruses” and bacteria “invade,” and the “immune system” has “killer cells” to “defend” us from these “attacks.” The “bugs,” in their turn, are constantly evolving into new “variants” to find new ways through our “defenses,” so we must be ever-vigilant against their latest mutation.

This language is very familiar, and it may even seem empowering. I have believed most of my life that I had a “strong immune system,” which explained why I almost never got “whatever’s going around.” But if there’s no such thing as “viruses” or “pathogens” that are continuously mutating to better attack me—if the disproven germ hypothesis and virology have no scientific validity—this metaphor ceases to explain good health and “sickness.” If there’s no such thing as “killer cells” or an “immune system” that mounts “defenses” against external attacks, the whole metaphor falls apart.

Thinking of our bodies this way is familiar because it partakes of the widely-accepted cultural paradigm that frames survival as a constant battle of species against species and individual against individual. In this paradigm, harm might come from any direction at any moment. This is what we learn about how our prehistoric ancestors survived, always on the lookout for the saber-toothed tiger that was ready to pounce and make them its dinner. In our times, it isn’t apex predators that want to kill us (unless we are living in a wilderness and we encroach on their territory), but tiny microbes that supposedly want to destroy our tissue (bacteria) or use our cells to endlessly replicate (“viruses”), causing serious symptoms and possibly death in the process.

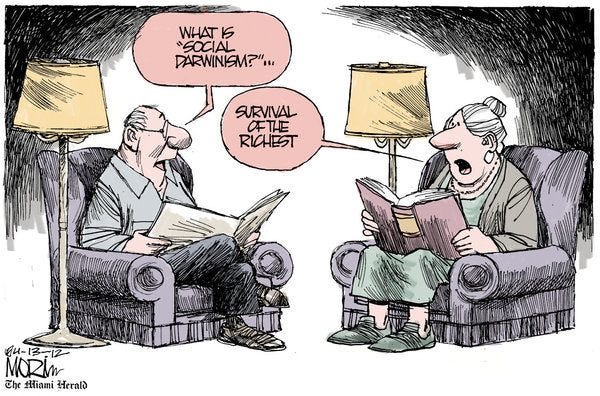

Our knowledge framework for understanding life this way comes from Charles Darwin’s The Origin of Species published in 1859. Phrases like “survival of the fittest” and “natural selection” are household terms whose meaning conveys that evolution is an “every individual for themself” endeavor—only the strongest survive. Even if it is read as “every species for itself,” which is how some say the force of evolution should be understood, there is still at the heart of it a sense that we are all competing against each other on some level for survival.

Some of the discourse about evolution and Darwin’s theory now says that he was misunderstood completely in regard to “survival of the fittest,” and that he actually spoke of ability to adapt to change as a primary factor in evolution. Even if that is true, however, evolution as a constant battle for survival is deeply embedded in our way of thinking. This may partly be because the 1% in the late 19th century saw Darwin’s ideas as a way to justify the class system, explaining that some were well off because they were more successful in competing for evolutionary survival, whereas those who had little were clearly unsuccessful specimens who should not be allowed to taint the gene pool. This is pretty despicable, but it predominated in social theory for decades, and is still present in Western culture. In recent years, we have seen eugenics being openly advocated again, as it was in the late 19th century, so these ideas have not gone away.

In regard to the reasoning for why “survival of the fittest” is a primary driver of evolution—whatever Darwin actually may have meant—common sense tells me that there has to have been much more involved than random mutations that were “naturally selected” because they gave those individuals a survival advantage. It’s impossible to believe that no matter how many millions of generations are involved, the eye of a dragonfly could have come about simply through random gene mutations, added one by one to the dragonfly’s physiology because they helped it survive better. The same can be said for flowers, the complexity of mammalian organ systems, and many, many other phenomena of nature.

Would we be here if our ancestors were more competitive than cooperative?

I also have serious doubts that our ancestors were as competitive as we have been told human beings are by nature. Even if there is truth in what school on all levels teaches about human origins (I think it is wise for us to view all of those stories warily, not assume their truth just because we learned them in school), I don’t see how our ancestors living in small bands could have made it through if their driving survival ethic were anything other than cooperation and mutual aid. In other words, if they were competing with each other for the food, say, instead of cooperating for survival, they would have been picked off by the saber-toothed tigers, and we would not be here today.

And speaking of saber-toothed tigers, if there’s any truth to that tiger-as-predator, human-as-prey aspect of the story, I am certain that existential threats from saber-toothed tigers were not the only or even the main formative influence on how humans evolved. It seems obvious that when we look at the past through the lens of the present, we will inevitably apply our current-day framework to what we’re looking at. It would be almost impossible not to. Western culture has been competitive as well as greedy and cruel for many centuries. So it should be no surprise that anthropology, history, evolutionary biology, and other disciplines looking at the human past have argued that ancient people were competitive, greedy, selfish, and war-like.

Was it really that way? I’d suggest, at a minimum, we allow for the possibility that it wasn’t. I would say that we’d do well to consider whether viewing ourselves as always potentially under attack and competing for survival is the best way to live everyday life (PTSD, anyone?).

Is it a dog-eat-dog world?

Questioning these narratives is about more than how we understand our human origins, though. It’s about how we understand ourselves in relationship to the rest of the natural world, including microorganisms and the processes of life that take place in our bodies every second of every day.

Despite significant popularization of recent scientific understandings that we have a microbiome not only in our gut, but everywhere in and on our body, microbes are still thought (even by most doctors and scientists) to be the causes of disease—and for this reason, these microscopic denizens are surrounded by an aura of fear. But casting these trillions of microorganisms as even potentially the “bad guys” alienates us from them and what they do to keep us going. Being afraid of our microbiome keeps us thinking of them as our enemy, and sends us back again and again for more “ammo” from the drug store—which only interferes with their work and pushes what they are trying to clean up deeper down. Like compressing the garbage by packing it more tightly, hoping it won’t break out the sides of the bag.

And obviously, if we don’t understand the microbes in and on our body as essential to our health and well-being, we also don’t understand that we actually have a conscious, active role in how they keep our bodies functioning. Viewing them as the enemy precludes an understanding of how we can support and nurture the tiny life forms that make up a significant percentage of the cells and the DNA in our bodies, so they will keep doing their thing to maximize our health. We can do this, for starters, by not suppressing uncomfortable symptoms, but letting them run their course. All manner of healthy habits around eating, moving, thinking, connecting with others, having a purpose, etc., support our microbiome, too.

If we can stop characterizing our relationship to the other species we share this planet with, including microscopic beings, as a battle, we can start to see other possibilities for what they are doing and what role they play in our “illnesses.” And we can do away with a vast amount of completely unnecessary harm through medical practices and protocols, including vaccination, that are aimed at protecting people from fictional particles and tiny life forms that do not intend us any harm.

The fact that bacteria intend us no harm may be a new idea for those who have never questioned the disproven germ hypothesis. But the truth is, bacteria do not attack healthy tissue. Let me say that again. Bacteria do not attack healthy tissue.

Taking out the trash

When bacteria are present along with symptoms, such as when someone has “strep throat,” the throat tissue may have already been damaged by something else, perhaps breathing polluted air, or swallowing food or a food-like substance that damaged the tissue, or it may be that the tonsils, which are a part of the lymph system and are therefore a detox pathway, are trying to eliminate something. The bacteria came to do their job, which is to take out the trash—to break down the dead and dying tissue so it can be eliminated from the body. They do not, under any circumstances, attack healthy tissue. Healthy tissue is not their food. Dead and dying tissue is.

Strep bacteria at a site of damage in the throat are analogous to firefighters at a fire. They are present at the scene, but they did not cause the problem. They’re there to help. The kind of help they give at a scene where harm is happening is different, of course, and that’s part of why it’s harder for us to see that what they do is crucial.

It’s easy to see the heroism of firefighters, but garbage collectors don’t have that kind of status. What they do is ordinary and often nearly invisible, and we are so deep in the romantic, mythological war metaphor for how life works that we prefer the image of a “warrior” that comes to the rescue to a scavenger that consumes decay and returns it to the Earth (though I will acknowlege it’s understandable that we do). We tend to ignore or discount the creatures and life forms that get rid of the waste in ecosystems—soil microbes, fungi, insects, carrion-eating birds, and so many others in a natural ecosystem, for example—and likewise in our bodies. Warriors may be more heroic, but life and death is played out in the most everyday of ways throughout nature by the tiniest of creatures.

The mechanisms of our body are very adept at protecting our terrain from substances and influences that cause harm. These mechanisms, however, are not “killer cells” that attack “invaders” like warriors fighting off the barbarian hordes, but nuanced sensitivities and capacities that remove what is causing the harm and repair the damage the instant it is detected. Removing the cause of harm is done through what we call “symptoms,” and repairing the damage happens through the same process, which includes bacteria breaking down the dead tissue so it can be eliminated via one or more of those symptom pathways. A great deal of the time, when the damage is minimal or consists of ordinary cell death, there are no symptoms, and we are not even consciously aware of this activity that is going on every second within us, to keep every bit of our inner terrain clean.

Once we entertain the notion that the war metaphor is not a proper model for how we relate to our mirobiome, we don’t have to look far to see how pervasive this idea is in framing our understanding of life on all levels. When we can clear up this misperception so it no longer incorrectly frames our relationship with nature and each other, some fascinating possibilities open up for new ways to understand those relationships. In the next article, I will address how this metaphor of battle misleads gardeners and farmers about the role of insects and other “pests” in the growing of food. (Hint: it’s pretty much an exact analogy to the mistaken understanding the war metaphor gives us for the role of bacteria in our bodies.)

Thanks for reading! If you appreciate the ideas and questions raised here, please consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Yes, the war like thinking influenced the way science saw the issue. We have the same problems in physics, economics, and other fields that obsess over competition vs cooperation.

There's a Joe Rogan joke that there's less women inventors but they all invented things that make life better and easier. Meanwhile the men inventors are shooting for the moon and how to better blow things up! 😂

Instead of helping the body do it's job, to take out the trash, modern medicine treated the symptoms of natural processes.

It's like giving someone a pill to stop pooping.

Maybe that's why they call a lot of these control freaks anal retentive 😆 .

Another great article Besty.

Looking at disease through the war lense, also encourages people to not take responsibility for their health.

It fosters the belief that it is not them or their habits that lead to illness, rather it's these invisible germs lurking around every corner ready to pounce and attack them that are to be blamed. It's the enemy not me that is responsible for my state of health.

It is also an attitude that suits lazy people not willing to let go of their unhealthy habits.

Also, couldn't agree more with you re the competitiveness and or violence of our ancestors. I also think that narrative is false, and likely pushed to make handing over our judicial and executive powers to governments look like a good idea. Sort of like, "if humans were not governed they would tear each other apart over resources."

I think it all started with Thomas Hobbs and his social contract theory. It was he who argued that the state of nature was one of violence and conflict. What nonsense.