Herbs have no opinion whatsoever of ‘viruses’ or ‘pathogens’

They are here to help us, not by fighting, but by supporting our bodies’ processes

As an aspiring amateur herbalist and someone who has rejected the narrative of “viruses” and the disproven germ hypothesis, I am dismayed that most herbalists still seem to be operating inside that narrative. Various medicinal plants are labeled “anti-viral,” “antibacterial,” or “anti-microbial,” and I have not seen anyone suggesting alternative language in light of the nonexistence of viruses and the fact that microbes and bacteria are not pathogenic. This seems wrong to me on several levels: (a) it does not explain what herbs are actually doing in the body; (b) it participates in the war metaphor for health (see my post Life is not a battle); and (c) it seems almost insulting to the plants to misunderstand their actions so dramatically.

When I began to study herbalism last year, I somehow expected that people engaged in this alternative health care endeavor would not be fully entrenched in the virus narrative. However, I have heard only one prominent herbalist say that the disproven germ hypothesis is a false paradigm, and suggest that what herbal medicines labeled “anti-” anything actually do—what their herbal actions really are—is more in line with supporting a healthy terrain than killing or destroying other life forms.

Herbalists following the ‘Covid’ narrative

What is especially confounding to me is how so many herbalists have endorsed and furthered the narrative of “Covid-19” during the past four years. Every well-known herbalist I have heard speak about this (except the one referred to above) has used the official language and description of this so-called “disease” and the “virus” that supposedly causes it, including, in some cases, endorsing the ridiculous “lab leak” narrative. I had hoped I was joining a community of people whose deep knowledge of some very ancient and traditional modalities of health would have kept them well apart from the modern medical paradigm and certainly critical of what was being called “Covid.” But it seems that Western medicine has encroached quite heavily into herbalism just as it has into naturopathic medicine and has swept herbalism into the fold of its beliefs and practices.

Certainly, we have seen the majority of people and organizations that could be called “alternative” or “counter-culture” in any part of society—even in some cases the farthest-out alternative institutions and people—fall into line with the “virus” narrative and, inexplicably, even more so the “vaccine” narrative during the past few years. This includes (in my own personal experience) yoga studios, food co-ops, naturopathic doctors, small improv theaters, Waldorf schools, restaurants run by punks and hippies, somatic experiencing practitioners, and massage therapists. You can probably name additional ones. And herb shops and herbalists must be counted among them. I’ll confess that even after more than four years, I still find the whole thing baffling.

To be honest, this phenomenon may be easier to understand in the context of herbalism because it is a realm of health care, and one that increasing numbers of people are turning to when they are ill. Over the past couple of centuries, even before Rockefeller medicine came in, herbalists have been attacked by medical doctors as “quacks” and have even been imprisoned for “practicing medicine without a license.” Perhaps it is not surprising that the field in general has sought to make itself more acceptable to the mainstream—and less susceptible to persecution—by adopting some of the attitudes and practices of the persecutors.

Integrating traditional and scientific herbal knowledge

Indeed, there are many well-known Western herbalists (for example, Matthew Wood, Thomas Easley, and Sajah Popham) who are endeavoring to bring traditional herbalism as practiced for many centuries in China, South Asia, the Islamic world, Africa, Europe, the United States, and Indigenous cultures around the world together with modern scientific approaches that use chemistry and pharmacological knowledge to understand how healing happens. Herbalists like these and many others want to integrate the traditional knowledge and its ways of validating herbal actions, which include observation, the doctrine of signatures, alchemy, and even astrology, with modern understandings rooted in scientific methods of ascertaining what makes each herb effective.

It is typical for herbalists who are integrating Western science into their practice to talk about “terpenes,” “phytonutrients,” “polysaccharides,” and other chemical components of plants which have been identified as having particular effects. Very often herbal practitioners will explain how a given herb affects the body by citing its chemical constituents (though they do not advocate isolating such constituents and packaging them as treatments, the way the pharmaceutical industry does with drugs).

Plant chemistry—is it necessary to know?

I’m not saying that there’s anything wrong with knowing plant chemistry. However, I think too much of that focus may push aside to a lesser or greater extent the more intuitive and observational evidence for why plants work in certain ways. And I am quite sure that adopting the disproven germ hypothesis, including the existence of “viruses,” as an explanation for illness is out of tune with the historic, traditional, shamanic, and folk approaches to herbalism that were in use since ancient Greece.

It seems to me that relying on knowledge of plant chemistry can come between the person with a condition or situation in their body that is causing them distress, and the plant or plants that have the power to help. The positive effects of the plant are then attributed to the chemicals in it, and the synergy of the whole plant and the interaction between the plant and the person on a more spiritual level may be left out or minimized in the healing equation.

This exemplifies the tendency of Western science since the Enlightenment to take natural things apart in order to see how they work, as if each component could be separated from the whole both to be studied and to be applied. This is, of course, how the human body has been studied by scientific disciplines in the modern era, and it’s why so much of what we think we know about human biology is turning out to be wrong.

And to me, it is intuitively obvious that herbs do not help people who are ill by killing anything, regardless of which chemicals the plants may contain that have been identified as “anti-viral” or “antibacterial.” So what are they doing then? How are plants assisting in the healing of people who have so-called “viral” or “microbial” illnesses?

I have been studying herbs seriously for only about eight months. So I don’t know very much yet. With that disclaimer, I will offer some of my thoughts on this.

Herbs and terrain

As a proponent of the terrain model of health and disease, I start from the awareness that the body is always seeking homeostasis and knows what to do when anything gets out of balance. In that context, I see that herbs and plants support our bodies in their self-healing efforts. “Symptoms” of “disease” are the body’s efforts to cleanse itself of unwanted substances or influences or to heal injuries both internal and external. Unlike pharmaceutical drugs, which are specifically designed to suppress those symptoms and thereby (supposedly) eliminate the “disease” or heal the injury, herbs work to facilitate the body’s own efforts. They do this primarily by amplifying the body’s processes and easing the pathways of elimination.

For example, with common conditions attributed to “viruses,” such as colds and flu, what is really happening is that the body is attempting to clear out buildups of metabolic waste that result from normal functioning—cellular death that occurs millions of times every minute and requires bacteria to show up and break down the dead and dying tissue for elimination. In a healthy terrain, clearing out this waste is a matter of course. But damage from toxins such as heavy metals and EMFs can add to the usual amount of dead tissue cleanup that needs to be done, so the larger-than-normal amounts of metabolic waste needing removal activate the “symptoms” of colds and flu—coughing, sneezing, fever, sore throat, nasal congestion, etc.

Colds and flu are also typical in the fall and winter in colder climates when people move less, don’t get out in the sun, and breathe stagnant indoor air, so the processes in the body become sluggish and waste products build up. According to Daniel Roytas in his recent book, Can You Catch A Cold?, for many centuries the cause of “colds” and “flu” was thought to be exposure to cold weather, as is evident in their names (“flu” is short for “influenza di freddo,” Italian for “influence of the cold.”) I covered this in a little more detail in my post Contagion has never, ever been proven.

When this happens, herbs can increase circulation to move the built-up metabolic waste products out of the tissues faster (e.g., hawthorn flower or garlic) and open channels of elimination to get them out of the body (e.g., peppermint or dandelion). Diuretic herbs like stinging nettle help flush waste and toxins out of the body via the kidneys, and diaphoretic herbs like cayenne encourage sweating them out. Well- known herbalists from Hippocrates in ancient Greece to 19th-century American root doctor Samuel Thomson, as well as folk herbalists throughout the ages, felt that inducing a patient to sweat was a good way to heal almost anything.

Another way plants help us during body detox events is by soothing and easing the “symptoms” that make us uncomfortable when our bodies’ healing efforts are underway. Herbs like chamomile and lavender are relaxing and can help us sleep. Cough syrups made from onion or garlic and raw honey can soothe a sore throat and ease a cough, as well as being nutritive.

Similar things happen with everyday conditions that are not “diseases” per se, but for which pharmaceuticals are often prescribed or over-the-counter drugs are taken to get rid of “symptoms”—conditions such as constipation, headache, or joint pain. (Specifics of a person’s condition, energetics, and tissue states can indicate which of the many possible herbal remedies will be best in each case.)

When an individual’s diet, exercise, and other factors have led to constipation, reducing the body’s ability to eliminate waste through the bowel, herbs like slippery elm can provide some lubrication to get things moving.

When digestion has become sluggish—the person has inadequate metabolic “fire” and experiences bloating as well as fatigue—bitter herbs like dandelion and yellow dock root can stimulate the production of stomach acids to fire it up again.

Headaches can be caused by muscle tension or restricted blood flow in capillaries; they can also be part of a body detox process. Lemon balm, catnip, and chamomile, among many others, can help to relieve stress and relax the circulatory system.

Many of these herbs that I have mentioned are listed in herbal materia medica collections as having “anti-viral” or “anti-microbial” qualities. Since viruses don’t exist and microbes do not cause disease, I find it far more comforting and encouraging to know that these plants and others are not operating with an energy of attacking or destroying some foreign invader within me, but rather supporting and encouraging my body’s own processes. Hippocrates would approve.

It is also a component of herbal healing to know that my own daily habits of eating, exercising, sleeping, hydrating, knowing my emotional state, getting outside in the sun, and other personal actions and enviromental situations in my life are all factors in my overall state of health (i.e., my terrain). I have responsibility for my own health and for providing my body with what it needs to maintain that.

The body is wise; so are plants

There’s a common saying among herbalists that when you have lived in a place for a while, the plants that show up around you have something you need, and they have come to help you. I have found this to be true. Plants that have chosen to grow in the semi-wild areas of my yard include nettles, motherwort, plantain, violets, and ground ivy (a.k.a. creeping charlie). I have needed and used all of them.

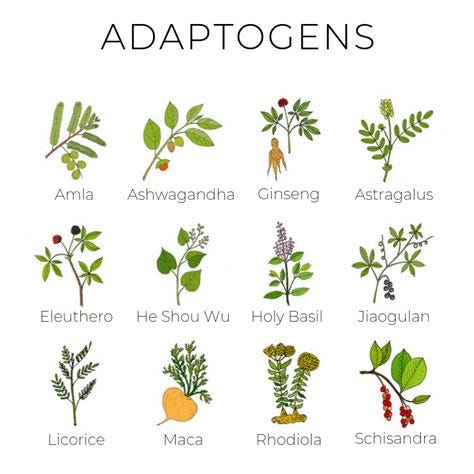

Along these same lines, on the more mystical side of herbalism, there are those who say that all of the plants know what to do for us—that they are already aware of what we need from them and are prepared to offer it. Some herbs are called “adaptogens,” plants that can do whatever is needed by the person who takes them. And some herbalists suggest that all herbs can be adaptogenic. They recount instances when they didn’t have the herb they needed for a specific condition, but another one that wasn’t normally used for that condition filled the bill.

This makes me think that the plants may actually know what we need better than we do, since we have been trained for generations not to know our bodies, and instead to put ourselves in the hands of scientific experts. We have been taught that life is a battle and nature is trying to kill us, so we have to fight back, even with violent means such as remedies that supposedly act like a search-and-destroy unit against so-called pathogens. Our internal senses have been dulled so we do not even feel when things within us are not working as they should, or if we do feel it, we don’t know how to interpret it or even less, what to do about it.

Getting to know herbs is a way to counteract all of this training. To me, the plants are mystical beings, maybe even multidimensional ones. I believe they are powerful, and that they are here to help us. I have even heard an self-described plant alchemist, Davyd Farrell, say that the plants, even though they have been here on the planet far longer than even our most ancient ancestors, already know how to counteract the very modern poisons that are being used against us, such as toxic pesticides, heavy metals, GMOs, nanoparticles, and EMFs. Their powers are not only what they have been known to do historically, but are increasing in a quantum manner to keep pace with what is needed from them now.

Plant communication: yes, it’s a thing!

And many plants are eager to connect with us—to communicate with us, to develop relationships with us. They are not merely green things that happen to have particular chemical or functional properties that we can benefit from. They are actually for us—on our side, in our corner. We don’t need to know their chemical makeup or whether they have actions that are “anti” any of the things we may be afraid of. We just need to listen to our bodies and to the plants themselves, observe how they affect us and our friends and family, and learn from the centuries upon centuries of knowledge about herbs and plant medicines that we have access to through books and courses and all the amazing herbalists who are teaching today (even the ones who think “viruses” are real).

And, though I could be wrong about this, I think that the plants appreciate it when we do not label them as anti-life in any way, but understand that they work positively for our benefit.

Thanks for reading. I look forward to your comments!

Recommended reading

John Slattery is an experienced herbalist who knows viruses are fictional and shares a southwestern US bioregional and vitalist perspective in his practice and educational efforts.

Here are some recipes to use garlic from another Substack herbalist, Sarah Donoghue.

Microbes are not attacking us—they are under assault by the same poisonous frequencies that we are. Roman Shapoval explains it all.

Lisa Strbac, author of Homeopathy Uncensored, is hosting an event in London with leading no-virus voices Alec Zeck and Dawn Lester as featured speakers. Her Substack is full of wonderful interviews and insights about healing without pharmaceuticals and the importance of responsibility for our health.

Excellent article Besty, so many very valid points.

This paragraph is particularly spot on : 👇

"This exemplifies the tendency of Western science since the Enlightenment to take natural things apart in order to see how they work, as if each component could be separated from the whole both to be studied and to be applied. This is, of course, how the human body has been studied by scientific disciplines in the modern era, and it’s why so much of what we think we know about human biology is turning out to be wrong."

What baffles me, is the fact that people who insist on adopting this reductionist approach when trying to understand how life and nature endures, are the same people who will agree that you cannot remove a cog from the inner workings of a watch and expect it to tell you the time.

Re the herbs, i have always wondered whether the practice of adding herbs to cooking has any significance beyond adding flavor. Especially seeing as many cooking herbs, oregano for eg, are known to have powerful effects on our terrain. As a simple example, perhaps to aid digestion. Could this be a thing? Maybe even in a adaptogen sort of way?

Ps : really loved the way you described the relationship plants have with us.

I understand your frustration that the mainstream narrative has infiltrated herbalism. As an herbalist with a nutrition focus, I agree with your article and have taught these concepts to my clients and students for a few years. I do this within a private community, as social media does not favour sharing about the innate wisdom that plants and our bodies have. Once people are in the door, I gently suggest that colds and the flu are the body's way to detox. A confusing concept at first! I focus on supporting the pathways of elimination. Given the amount of toxicity we are currently facing, it is a full-time job to help our bodies in this process.