What viruses tell us about human nature

Are we their 'prey?' And are we weak, depraved, inadequate, violent, sinful beings?

When I say that knowing viruses don’t exist can change everything, I mean that the belief in the existence of viruses connects to many other narratives that purport to tell us who and what we are as human beings. And these stories about us, in turn, connect with another layer of narratives supposedly informing us about the nature of reality. Understanding, or even questioning, that viruses and “the germ theory,” which I prefer to call the disproven germ hypothesis, are untrue often does lead to questioning of other received knowledge—questioning that can shift our perception of literally everything.

An example of how this chain of questioning, starting with viruses, can peel away layers of belief and assumption about ourselves and the world is the question of human nature. How does belief in viruses relate to our understanding of human nature? Keep reading.

‘Humans are fundamentally weak’

The disproven germ hypothesis and virology tell us a couple of significant things about reality (if we believe them). They tell us that disease is a random event caused by tiny microbes that can jump into us from almost anywhere or anyone and make us ill. We are entirely helpless and powerless in the matter. These microbes are everywhere, and we are even told that anyone and everyone is probably carrying some virus, maybe a deadly one, even though they don’t appear to be ill. So we are at the mercy of these microbes—there’s no way we can protect ourselves.

And this powerlessness is not limited to our susceptibility to viral disease. It extends to making us forever dependent on artificial means to stay healthy and even alive—medical system interventions such as vaccines, therapies, surgery, and pharmaceutical drugs. So in a subtle one-two punch, the virus narrative and the medical system that promotes it shape us as hapless victims dependent on that system for our survival. We are taught to think of ourselves as essentially children, unable on our own to take care of ourselves but needing “mommy medicine” in the role of a parent to provide what we need to stay alive. This dependence is real, clearly shown in the number of people who rushed to get an untested shot when told that a “novel virus” was loose in the world, and the number even now who can still be seen wearing masks as they were told to do in 2020.

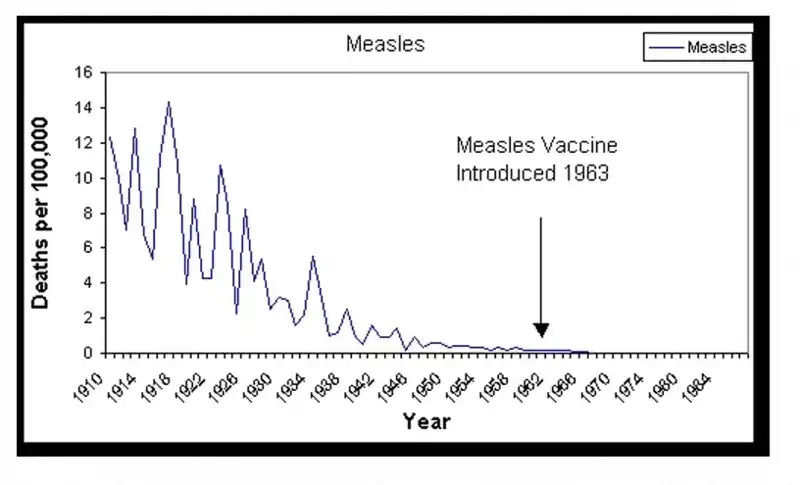

Think about the narratives we hear regarding vaccines and how they have “eliminated” various diseases and “saved millions of lives.” Vaccine developers are painted as heroes. But when you look at the actual data, diseases such as measles and whooping cough were already in steep decline when those vaccines were introduced. The narrative of vaccines, which exist only because of belief in viruses, trains us to believe that nature is trying to kill us with these deadly viral diseases, and it is only due to the innovations of modern medicine that millions of us do not continue to die from them.

‘Humans are morally weak’

So the narratives of the disproven germ hypothesis and virology provide fundamental arguments for our inherent weakness as living beings on this planet. But the weakness we are taught to believe is part of our nature is not limited to physical susceptibility to disease. It also includes emotional or spiritual susceptibility to behaving badly—acting in ways that harm ourselves and others. We are supposedly innately prone to greed and other “lower” emotions and behaviors, from disrespect and meanness to violence and murder. In this narrative, we are predisposed to trying to fulfill our own desires at the expense of others and causing harm on an individual scale, such as stealing and fighting, as well as a social or national scale, exemplified by cutthroat business practices and war.

In short, we are supposedly cruel, violent, and destructive by nature, prone always to making bad decisions, and it is only civilization that provides a veneer of control so we don’t simply kill each other (Freud, Civilization and Its Discontents). This is closely related to the religious narrative of “original sin,” or, in whatever terminology it is expressed, the idea that human beings are inherently not good enough and require outside intervention from some kind of deity to be acceptable.

Because in this narrative depravity arises out of fundamental weakness in human nature, I draw a thread of connection between the notion of depraved human nature and our supposed inability to protect ourselves from assault by microbes. Our belief in our own depravity is a near cousin to our belief in our own physical weakness.

‘Humans are a random accident’

The narrative of evolution is another contributor to the model of human nature as weak, depraved, and inadequate. In this narrative, human beings have come into existence through an uncountable (but ridiculously huge) number of random genetic mutations over eons of time. Everything about us is accidental, random, disconnected. Some see a type of intelligence at work in this story, but meaning on a deeper level is hard to find in this model.

And in evolution theory, competition is a central drive, so the negative and destructive aspects of competition—such as war and unethical business practices—are by definition natural and inevitable as we evolve.

I want to unpack “competition” a bit, because it is a complex concept. Competing can be a way to sharpen our skills. It can be a kind of incentive to keep our bodies in good condition. Seeking to create better ways to do things is certainly a way in which competition provides positive motivation. Friendly competition, such as in athletic games, can help everybody improve their health and skills while bonding through an enjoyable activity. But competition can also easily slide over into a focus on winning rather than improving one’s own physical prowess, which opens the door to cheating and even violence. We see this everywhere today, in sports, business, politics, and other arenas of life.

It seems evident to me, however, that competition is not the fundamental driving force in human survival. We are hardwired for cooperation and mutual support, for helping each other survive and improving conditions for all, not only for ourselves or our family at the expense of others. In the context of conventional notions of evolution, if competition and not cooperation were our default setting, our ancient ancestors would have been picked off by predators because they tried to save themselves instead of helping each other survive. In that case, we wouldn’t even be here.

Thinking outside the narrative of evolution, however, competition as a fundamental force in human nature seems even less likely. In Darwin’s theory, competition is the driving force in evolution—it is, he says, how each individual and each species survives. The mouse and the owl push each other to develop their capacities, the mouse to be faster to outrun the owl, the owl to improve its vision to see the mouse better. The competition inherent in this predator/prey relationship is a dynamic of how evolution supposedly works.

Are ‘viruses’ predators?

If it is true, as is sometimes said, that viruses and humans are in a predator/prey relationship, the same dynamic should be at play as with the mouse and the owl. But we have no way of escaping from the things called viruses, or of sharpening any of our abilities to avoid being attacked by them. Their attacks are entirely random, with no pattern to which we could learn to adapt. Our “immune system,” even if it existed, is a function of our body which varies in its strength from day to day. It could not be described as a skill or capacity we could develop (through random mutation) and pass on to our descendants to help us avoid attack by viruses. So if “viruses” were really a predator and we their prey, B.J. Palmer’s comment would have come true long before now: “If the germ theory were correct, there would be no one living to believe it.”

Social Darwinism

Another way that Darwin’s evolution theory has promoted an image of human failure and incompetence is its application to society. Although “survival of the fittest” doesn’t really apply to humans, as indicated above (we would not be here if our ancient ancestors competed with each other instead of cooperating for survival), this theory has been applied to explain why some people are more financially successful than others—and, by extension, more fit to survive. In this narrative, the man or woman with greater success in making money—the one who is more fit—survives, and the less successful suffer because they are less fit. This is the thinking of social Darwinism, a close relative of eugenics, the idea that some people are inherently more fit and therefore worthy of survival and others are less fit, and that material wealth is a significant indicator of that worthiness/fitness. (So-called “racial” differences are another indication.) This idea was strong in the late 19th century, and it has not gone away.

Evolution replaced origin stories

To me, this theory of Darwin’s is highly questionable. It seems to have arisen at a time when the narratives of religion were no longer adequate to explain the differences in wealth and status among humans in society. Religious answers to the existential questions of who we are and why we are here were also falling out of favor in the wake of the “Enlightenment” which elevated science to replace religion. When the situation of masses living in misery while a few lived in luxury could no longer be attributed to divine order, a new model was needed. The new model also offered an alternative explanation for the origin of human beings that was detached from the sense of intention found in every creation myth from every culture throughout history, as well as any sense of there being inherent good, truth, and beauty in the universe.

One other aspect of how we understand ourselves as humans also connects to this idea of inherent weakness in human nature, and that is the idea that we have a tendency to “go along with the crowd” and also to defer to outside authority especially when that authority is wearing a white lab coat. These will require some unpacking, so this will be the topic of my next article.

Are humans really weak and hapless?

I hope I have clarified the connection I see between questioning and even disbelieving the narrative of viruses and deeper questioning about what kind of being humans are. The thread I am tracing is the weakness, inadequacy, and dependency that are woven into the disproven germ hypothesis, continuing through a weakness in character that religions call original sin, through a debasement from created being with an origin story into a random accident, and to an explanation for socially stratified suffering and misery that makes it our fault.

Through all these concepts and narratives, the thread of innate inadequacy contracts our vision of what a human being is—of what we ourselves are—into a very small space. Keeping our self-understanding within these narrow boundaries ensures that we will not ever see or experience ourselves as powerful, capable, in command of our lives, and possessing a dynamic creativity. We will not see ourselves as virtuous and noble beings. We will not even dare to think that we might be able to dream new worlds into existence. Instead, we will continue dreaming the current dystopia because we believe it is inevitable because its flawed, heartless, and destructive character is a reflection of our own depraved nature.

Individually, we can dream a different life for ourselves, and make it real with our powerful inherent creativity. And collectively, we can dream a different world into existence, a world where kindness, generosity, true equality, and true prosperity are the predominant values, not violence, cruelty, greed, and selfishness. And it can all start with allowing ourselves to question the existence of viruses.

Thanks for reading. Please leave a comment. And if you aren’t already a subscriber, please do subscribe, and consider a paid subscription. Thank you so much.

Recommended reading

I highly recommend Cate Montana’s Substack, Cracking the Matrix. Here are a few of her recent articles.

Hi Betsy,

Since I stopped believing in "viruses", and other things, I have felt very positive and you have just articulated why for me. It is the sense of empowerment, exactly. Thank you.

We are not hapless victims, and we have much more autonomy than some people realise. We are also not the inherently faulty units the Dark Lords and their minions think we are, and that perhaps says more about them than us.

I hadn't heard the term social Darwinism, but I agree, it fits very nicely with eugenics, and does still appear to be supported. In most cases, this wealth is inherited and the product of many generations, not one person, and one's worthiness simply an accident of birth.

Blessings,

Janey

Yep, human nature has been misrepresented by every piece of crap corrupt leader of society, including the current fools in power.

They were so convinced that they ignored facts in favor of proving their ASSumptions.

https://robc137.substack.com/p/the-milgram-experiment-and-how-we

Oh and genetics, another pseudoscience like virology and quantum theory. Even DNA matching is inaccurate when done double blind.

https://controlstudies.substack.com/p/the-dna-hoax-0a2