Learning how to think: logical fallacies

Once you learn to spot them, you will see them everywhere--even in your own mind

One of the reasons I say that knowing viruses don’t exist changes everything is that it can ignite a process of questioning—questioning what you think you know about health and illness, but also questioning how you know what you know about anything. This starts with realizing that you have been accepting what you’ve been told by experts, teachers, and other authority figures about viruses, disease, and contagion, and that you have believed those authority figures because they “know more than I do.” And just like that, you become aware of the first logical fallacy that has misguided you: appeal to authority.

We were all raised that way. What we learn in school is settled knowledge because smart people figured all that stuff out and wrote it down in books. We just need to learn it, and we’re good. And we are conditioned to accept that what experts tell us must be true, especially if they are dressed in white coats, because they have studied for years and years and have a highly respected position in society, so they couldn’t be stupid and they certainly wouldn’t be lying!

The modern education system does not teach us about logical fallacies. This is on purpose, of course—since knowledge about logical fallacies can be a significant aspect of critical thinking. I used to think that logical fallacies were something you learned if you took a philosophy course. I associated logical fallacies with classical Greek education—the trivium and quadrivium—not something that is typically taught in the modern era. Certainly not something I ever encountered in my schooling. It seemed like arcane knowledge, mainly for the ivory tower, not really relevant to a person navigating everyday life in the 21st century.

But interest in logical fallacies seems to have grown during the Covid era, certainly so among those who are questioning the dominant narrative. And I think it is because of this first logical fallacy—appeal to authority. Many are questioning the knowledge we have been handed by authorities about viruses and such. And if our trust in these particular authorities is now in question, how about all the others?

I haven’t taken a philosophy course, but I have studied rhetoric, so I understand the principles of persuasion and how they apply in argumentation. And argumentation is the terrain we are on with propaganda. I want to credit Dr. Jordan Grant for much of what I have learned about logical fallacies, especially as they have been used in virology and the Covid scam. If you’re interested, check out his video presentation from 2022 here, and a recent in-depth interview with Alec Zeck of The Way Forward here.

I call “appeal to authority” the first logical fallacy because it is the one that, for me at least, opens the door to how we have been persuaded to accept the received knowledge about how the world works and how our bodies work even if what the experts are saying goes against our own sensibilities, including our reason. Getting us to “appeal to authority” for our own behavioral standard was the main form of coercion during the recent plandemic to persuade the public to go along with the ridiculous protocols of masking, social distancing, and, of course, getting the jab.

No evidence was offered for why any of these protocols should be obeyed, but only the word of Anthony Fauci, the dean of your university, the administrator of the hospital where you work or where your loved one was being treated, or your primary physician, and later your mayor or your governor who felt empowered as an authority figure to impose various restrictions on your freedom. And we need to add the managers of all the businesses that also imposed these restrictions.

I had to get that rant out of the way. I diverged a bit from logical fallacies with this focus on how appeal to authority is used coercively on an entire population. Appeal to authority is also, along with a number of other logical fallacies that I will describe below, used in arguments between individuals and even in academic discourse such as papers about virology. It can even be what we do ourselves when making decisions about anything in our lives. How often do you doubt your own sense of the best course of action in any context and instead defer to an outside authority? It’s deeply ingrained.

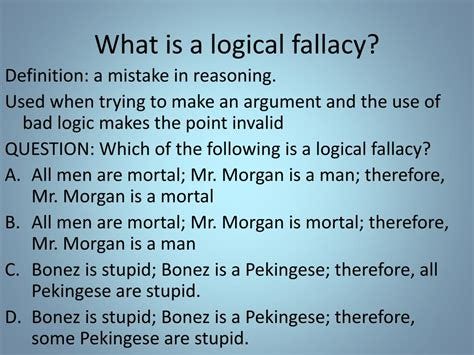

We could get way into the weeds with unpacking what a logical fallacy is and the difference between its uses in logic and in rhetoric, though they are related. Here are definitions from each perspective.

Scribbr (editing and proofreading website) defines “logical fallacy” this way:

A logical fallacy is an argument that may sound convincing or true but is actually flawed. Logical fallacies are leaps of logic that lead us to an unsupported conclusion. People may commit a logical fallacy unintentionally, due to poor reasoning, or intentionally, in order to manipulate others.

Philosophy Terms (philosophy website) says this:

Logical fallacies, or just “fallacies,” in philosophy, are not false beliefs; to oversimplify, they are logical errors in argumentation, reasoning, explanation, rhetoric, or debate.

Some are actual errors of logic, but other argumentation errors usually included in the category of logical fallacies are not so much logical as verbal or informal. Rather than parse out the difference, I’m going to list and describe the ones that are most commonly seen in the Covid era regarding the existence of viruses and contagion. These fallacies also show up in discourses and arguments about other topics. Learning to recognize them can help us not to be taken in by propaganda and public efforts to persuade us to behave in certain ways, as well as enabling us to spot the errors in reasoning that we hear all around us and that we do ourselves. In other words, understanding logical fallacies can help us learn how to think more clearly and use our innate capacity to reason to understand what is going on around us.

The first group are some of the fallacies that were visible in the arguments about the existence of viruses and contagion. The second group are those that have less to do with logic per se and more to do with the rhetoric of persuasion and with unrigorous thinking.

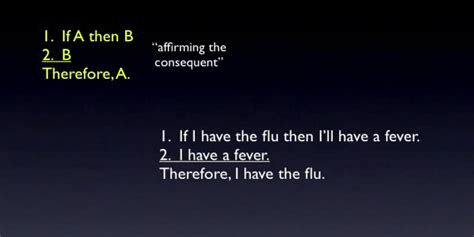

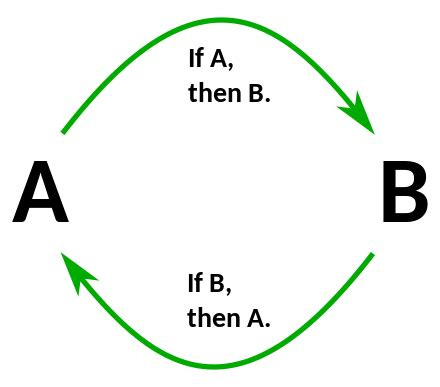

Affirming the consequent

In the logical statement, “If A, then B,” the argument can only go in one direction. If you start with “B,” and argue “If B, then A,” the result is erroneous. “If there is a virus in this bodily fluid that I am putting in this cell culture, then there will be cellular death.” The truth of B—cellular death—would prove the truth of A—a virus. This could work, if they already had a virus in that fluid and their experiment was to find out if it killed cells in a cell culture. But they don’t know whether there is a virus in the fluid; they assume it is there, and at the same time they are trying to prove that it’s there. Yes, it’s convoluted. What virologists do is to argue in the opposite direction: “If there is cellular death, it was caused by a virus in that bodily fluid.” They’re using affirming the consequent logical fallacy to claim that they’ve found a virus which they have not found.

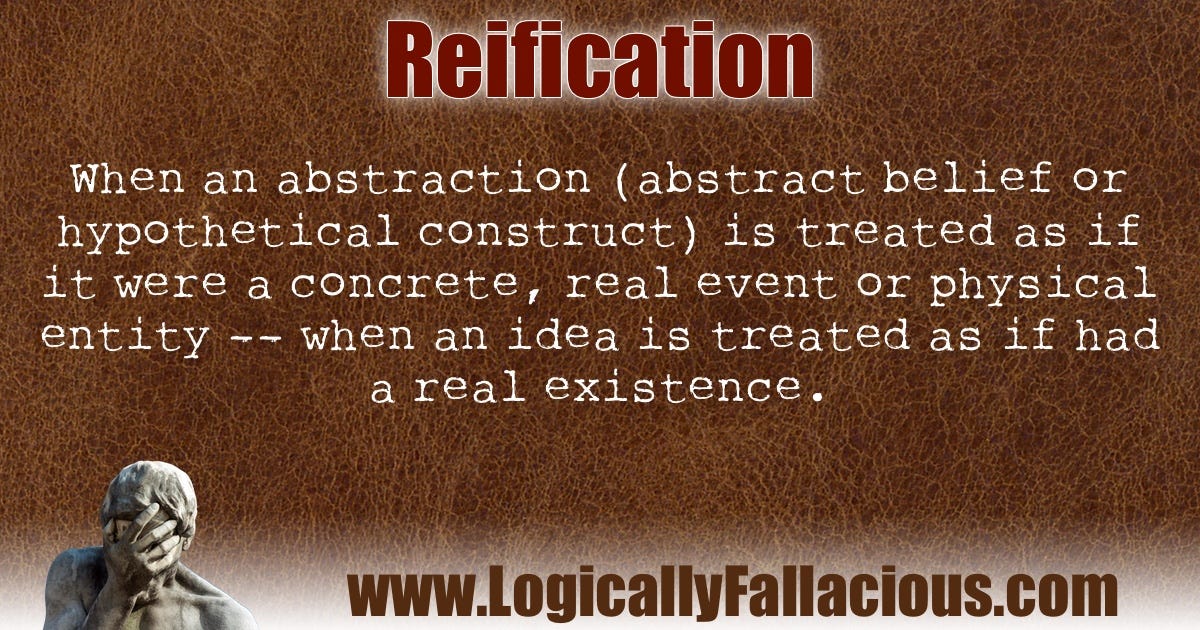

Reification fallacy

Reification is treating something that is abstract or conceptual as if it were real and had concrete attributes. In science, this especially happens with models. It occurs anytime anyone says that an inanimate object or an idea or abstraction can speak, feel, know, see, or otherwise act as if it were animate. “This climate model gives us 10 years till global meltdown.” “The science tells us viruses can live on the surfaces of groceries for three days.” Virologists commit this fallacy when they point to the genome assembled by computer software and calls it a virus.

Circular reasoning

This one should be easy to spot: using the conclusion as a premise. “A happens because it is caused by A.” The arguer starts with what they are trying to end with, and then when it’s there at the end, claim they have proved it. In virology, the circular argument is made when the virologist takes bodily fluid which they claim has a virus in it but not isolated from the other components of the bodily fluid, puts it in a cell culture, and when there is cell death in the culture, claims it was caused by a virus. We put a virus in, and lookee! We found a virus! This is the way, according to what I have heard and read from people who have actually looked at all the papers, that every virology paper makes its argument for the existence of the virus in question. It’s right there in the methods section for all to see.

The circular argument and affirming the consequent are both similar to another common logical fallacy, begging the question, which means assuming the truth of that which the argument is supposed to prove. In virology, the existence of a virus is always assumed before any experiment even starts. (The phrase “begging the question” is often misused to mean posing a question, when an argument leads to a very clear question that then needs to be answered. This is not “begging the question” as I thought it was for decades and I have heard many others use it. Just wanted to clarify that.)

Burden of proof reversal

Those who argue for a terrain understanding of illness and health experience this frequently. “If there are no viruses, why do people get sick?” It’s natural to ask this, but burden of proof reversal happens when the meaning is, “If you don’t have an alternative explanation, then viruses must be the cause of measles, rabies, chickenpox, flu, etc.” The burden of proof is always on the party making the positive claim—in this case, the positive claim is that viruses exist and cause disease. The burden of proof is not on the one arguing against that claim. This is because it is impossible to prove a negative.

Burden of proof works the same way in the court system. It is the prosecution that must prove their claim that this person committed this crime. The person accused of the crime is not required to prove that they did not do it. (Of course, we know that the court system is heavily rigged and actually operating in a way that is not in our best interest, but the example helps to explain burden of proof reversal and the difference between a positive claim and a negative.)

Those questioning the positive claim that viruses exist are not required to provide a replacement theory or explanation. Yet, in every argument or conversation I have seen or heard on this topic, proponents of virus existence do not offer evidence for their claim or even refute the other side’s points, such as addressing the circular reasoning and affirming the consequent fallacies that are inherent in their methods; rather they use other logical fallacies such as ad hominem attacks and appeals to authority in responding to those arguing that virus existence has never been proven.

Many logical fallacies have less to do with the specific premises of logic and the syllogism (e.g., “If A, then B”), and more to do with how people think, make associations between things, jump to conclusions, behave emotionally, and so on. Understanding these can help us not only see how we are being manipulated by propaganda, but also where our own thinking is a bit sloppy or even unconscious.

Appeal to authority

We’ve seen how this operates in the context of propaganda. In the context of any idea or course of action that you are discussing with someone else or thinking about yourself, appeal to authority is basically saying, this must be true or good because the experts say it is. We saw this big time during the plandemic, with people revering Anthony Fauci and following his dictates as if he were the spiritual grandfather of humanity as well as the reification of “the science.” It can also come into play on an individual level. Are you deciding about this, whatever it might be—going on a trip, taking this medication, joining this class, etc.—based on what you feel, what your body is telling you, what your inner authority says? Or are you appealing to some external authority in your own thinking—not just for added information, but because it is an authority on this topic? It’s a question I feel is worth asking because I catch myself doing this.

Bandwagon fallacy

This is similar to the appeal to authority, except it is the appeal to popularity. A lot of people are doing this or agreeing with this, so it must be good and true. We saw this writ large with masking, social distancing, and getting jabbed. Everyone is doing it, so (maybe) I should, too. I suspect this was operative on the level of organizations also. Those other stores are requiring shoppers to mask, so we should, too.

You could say this is a factor of human nature, that belonging and being part of the tribe is a very strong motivating force in our psyches, and taking a different direction can feel very risky. Being shunned and excluded is extremely painful, as many who did not get on the bandwagon with the various Covid protocols know all too well. And of course, this human propensity was heavily exploited by those external authorities to coerce the behavior they wanted.

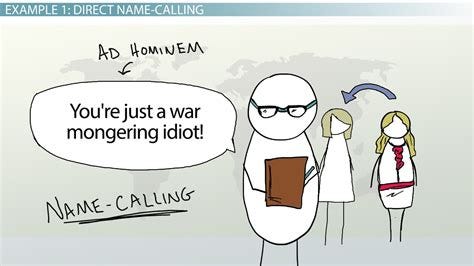

Ad hominem fallacy

Anyone who has spent any amount of time on social media in the past decade and a half has probably experienced this, or at least witnessed it. It is also prevalent in personal arguments between people about any topic when one attacks the other personally rather than arguing the points that are being made. Usually, it seems that this happens when the person making the ad hominem attack doesn’t have any argument to stand on, and instead of refuting the other person’s points, they tell their opponent that she is stupid, doesn’t have enough education on the topic, is a conspiracy theorist, is somehow personally motivated to take the position she does, wears ugly shoes, or any other comment that discredits the person rather than addressing their points.

Ad hominem is easy to spot, and it’s also easy to fall into in one’s own thinking.

Hasty generalization

This one is more informally called “jumping to conclusions.” It happens when someone draws a conclusion based on inadequate evidence. One way this happens in argumentation is when a person hears only part of the argument and thinks that they know what it says, then responds or reacts to that small part rather than understanding the full argument. Often this can happen when the first part of an argument sounds like something you have heard before and have an opinion about. When I was teaching college writing, this was a common occurrence when students would read an essay and be asked to write a paper responding to it. We spent many hours in class learning how to read to understand the full argument and not stop at “I like or agree with this,” or “I don’t like or disagree with this.”

This is also something that is very easy to do, and it’s good to catch ourselves. Of course, the first reaction is always liking or not liking, agreeing or disagreeing. But it’s too easy to stop there and not actually understand the argument the other person is making. It’s probably more complex and nuanced than your knee-jerk reaction allowed you to see.

There are some other common logical fallacies: the strawman argument, arguing against something the other person did not say; the red herring, shifting the argument by introducing an irrelevant point; equivocation, using a word ambiguously or in two different ways and exploiting the confusion; post hoc ergo propter hoc, this happened after that and therefore that caused this (correlation is not causation); and false dilemma or false dichotomy, there are only two possible choices and they are diametrically opposed.

Knowledge and freedom

One of the things I appreciate so much about the growing discourse that viruses have never been proven to exist is how it has expanded to encompass a wider range of knowledge than just viruses. Questions of epistemology—how do we know what we know—and questions of freedom and sovereignty have come up as offshoots of the inquiry about viruses, the disproven germ hypothesis, and contagion. I find that we are living in a time when everything we thought was real is coming into question, and the willingness to question the existence of viruses puts one in a better position to consider what knowledge and freedom really are. It can change everything.

And learning to think more rigorously is a good thing! Thanks for reading. Please consider becoming a paid subscriber, and share any of my articles with friends and family. There is no paywall here.

More good reading

Enjoy some of Demi Pietchell’s recent meme drops. They just keep getting better!

Interesting article, Betsy. If only, though, if only, we only needed to understand logical fallacies. You show images from two sites on logical fallacies, www.logicallyfallacious.com and www.yourlogicalfallacyis.com. The owners of both these sites, Dr Bo Bennett and Jesse Richardson, respectively, expert as they may be on logical fallacies and cognitive biases, still manage to be totally mainstream thinkers - Bo banned me from his site although I am always perfectly civil and reasonable and when he argued with me he shamelessly and seemingly with no recognition lapsed into typical fallacies such as ad hominem and appeal to authority. I wrote to Jesse ... and, of course, no response. I just came across a link to this article on Jesse's LinkedIn.

https://www.clearerthinking.org/post/can-this-article-change-your-mind-about-how-minds-change

It starts with: "Whether you know it or not, you have a scale of believability for conspiracy theories in your mind," and there's a Conspiracy Test you can do. I started to do it but it was so infantile and sillily presented I just abandoned it. You might have more grit in pursuing it if you are so inclined.

I invite you to sign up to logicallyfallacious and go a few rounds with Bo. Would love to see that! Let me know if you do.

I think this quote from social psychologist, Carole Wade, really applies: “People can be extremely intelligent, have taken a critical thinking course, and know logic inside and out. Yet they may just become clever debaters, not critical thinkers, because they are unwilling to look at their own biases.”

To my mind you don't have to understand logical fallacies at all if you're essentially an intellectually honest thinker because when you're intellectually honest you naturally don't fall into logical fallacy ... but, unfortunately, most people aren't. However, it's still good to know both logical fallacies and cognitive biases.

I wrote a post, 12 logical fallacies unmasked in the use of the terms "conspiracy theory" and "conspiracy theorist" (https://petraliverani.substack.com/p/11-logical-fallacies-unmasked-in) and these are the 12 logical fallacies covered.

1. The authorities decide which events are conspiracies - the Appeal to Authority fallacy

2. Only the majority expert voice counts, the minority expert voice is to be derided and ignored - the Appeal to Common Belief fallacy

3. Professionals do not make claims of conspiracy nor do they theorise - the Strawman fallacy

4. Refuters use the more specific and appropriate term, “psychological operation” or psyop - the Definist fallacy

5. Selecting the obviously invalid argument - the Cherry-picking fallacy

6. OMG! You’re one of those tinfoil-hatted people! - Argument from Intimidation fallacy

7. Your reasoning is based on bias, mine is rational - The Bias Blind Spot

8. Is the fact of conspiracy the main concern? - no, it’s the Big Lie fallacy technique used for millennia to control our minds

9. The sophisticated Big Lie - the addition of the False Dilemma fallacy

10. If those in power had done it they would have … - Hypothesis contrary to fact

11. That’s insane, that cannot be true - Argument from incredulity

12. When the rule is that they must “tell” us the truth underneath the propaganda how is the rejection of the narrative in the realm of “theory”? - The Loaded Question fallacy

My local pharmacist was wearing a mask yesterday. She gave her usual jolly greeting through the face nappy as if everything was perfectly normal. I immediately responded with why are you wearing a mask. You know there's absolutely no reason for wearing one. Her tone and demeanor immediately shifted to embarrassment and shame. Her coworker (maskless) popped his head around the corner with a look on his face. Yes, that look. I continued business as usual with the coworker. The masked crusader stood around with mask now around her chin but still sidelined. I resisted the urge to unload information this time (as I have done on other occasions). It always comes across as an unsolicited lecture and I tend to go way too far down that path, all in one go, for the normie mindset. These occurrences usually end with an abrupt change of subject or a decidedly rapid exit by the normie if an escape route is available. Anyway, thought I'd share for comment. This is still the situation in all medical environments here in Spain, but I wonder if the tide is shifting on the mask issue even in these bastions of illogical protocols, these pockets of self harm, these islands of incredulity. Maybe that's all it takes to break the spell. Immediately ask the mask wearer why they are still following along. They are in a tiny minority now even though they cluster together in their places of work. If enough people simply walk in and ask them why they are still playing dress up we could break the final cult members before the next plandemic kicks off. And then all people have to do is refuse to be tested in any way.